Promoting Mental Health

Mental health is more than the absence of mental illness. The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her society.” The Canadian Mental Health Association estimates that one in five people will experience a mental health problem over the course of their lifetime (www.cmha.ca). Among youth, data suggest that 70% of those in need of treatment do not receive appropriate mental health services (National Association of School Psychologists, 2003). As indicated in a Canadian survey recently referenced in the Montreal Gazette (October 5, 2010), this is in part due to the fact that mental health resources for youth are scarce to non-existent.

Although research in the field of youth mental health is still in its infancy, it is known that the onset of some disorders can be traced to childhood and adolescence. Early identification and effective intervention can serve to enhance quality of life issues for those affected by mental illness. A critical component underlying effective intervention is psycho-educational in nature, with strategies designed to minimize stigma and educate all involved about the realities of living with mental illness.

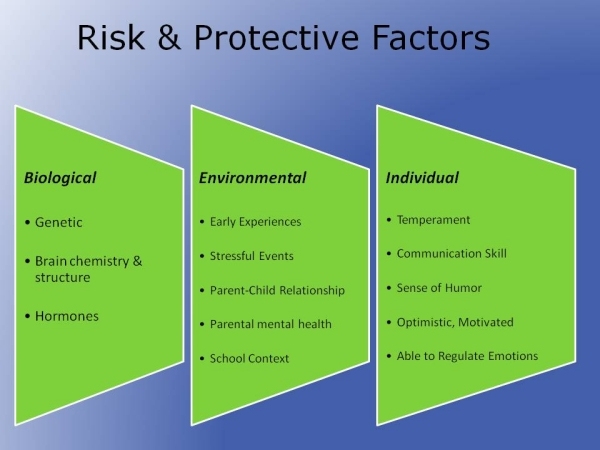

Increasing protective factors to mitigate risk factors can go a long way in reducing the long-term impact of such challenges.

Promoting Positive Mental Health in Schools

Recent research in health and educational domains asserts the importance of moving beyond a problem-focused approach to embrace a more positive view of mental health. This shift involves the recognition that children’s and youth’s state of psychological well-being is not only influenced by the absence of problems, but also by the existence of factors that contribute to positive growth and development. From this perspective, positive mental health in schools underscores an approach that mental health is more than merely an absence of mental illness. Rather, its aim is to encourage a healthy mindset within our students and staff by providing strategies to increase overall psychological, emotional and physical health and well-being.

Positive mental health has been described as “the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity” (The Public Health Agency of Canada, 2006).

The emergence of a positive mental health perspective has shifted the focus of educators and health professionals from a preoccupation of repairing weaknesses to the enhancement of positive qualities. In schools, positive mental health initiatives/programs focus on increasing students’ understanding of mental illness and preventative strategies though the adoption of a healthy lifestyle. Enhancing the quality of life of children and youth through prevention approaches has been shown to be very effective at reducing the risk of developing mental health-related concerns.

Positive mental health approaches in education and health share common principles or values related to fostering the psychological well-being of children and youth. These include:

- Children and youth have inner strengths and gifts that support their capacity to initiate, direct and sustain positive life directions

- Engagement and empowerment are critical considerations for facilitating positive development or change

- Social contexts and networks provide important resources and influences that have the capacity to contribute to and enhance their psychological well-being

- Children’s and youths’ relationships with adults and peers that contribute to psychological well-being are characterized by interactions that convey genuineness, empathy, unconditional caring and affirmation

Positive mental health approaches and practices contribute to improve physical and emotional developmental outcomes in children and youth. The range of educational, physical health and psychosocial benefits to students related to the implementation of positive mental health perspectives and practices within schools include the following:

- Identification and effective management of emotions

- Enhancement of positive coping and problem-solving skills

- Creation of meaningful and positive learning environments

- Increased participation in structured community recreational and leisure activities

- Increased understanding and de-stigmatization of mental health conditions

- Enhanced opportunities for children and youth to demonstrate age-appropriate autonomy and choice

- Increased involvement in structured and unstructured physical activities

- Reduction in high-risk behaviours (e.g. alcohol and substance use)

- Enhanced academic achievement and school attendance

- Increased academic confidence and engagement

- Improved mindset and relaxation strategies

Schools play a key role in delivering services related to positive mental health. As children move into their early and later teen years, schools may play an even more significant role in this area in influencing youth. A comprehensive school mental health framework involves a whole school approach that can include strategies in the following areas:

- Social and physical environment

- Teaching and learning

- Healthy school policies and promotion of prevention initiatives/programs

- Partnerships with family and community

Some general guidelines that schools can adopt which have been shown to increase positive mental health among students include:

- Enhance learning outcomes

- Uphold social justice and equity concepts

- Provide a safe and supportive environment

- Involve student participation and empowerment

- Link health and education issues and systems

- Address the health and well-being of all school staff

- Collaborate with parents and local community

- Integrate health into the school’s ongoing activities, curriculum and assessment standards

- Set realistic goals built on accurate data and sound scientific evidence

- Seek continuous improvement through ongoing monitoring and evaluation

For more information on how to implement positive mental health practices in schools, click on the following links:

For more specific prevention initiatives/programs and strategies in the area of mental health promotion, click on the following links:

To learn more about mental health, click on the following link:

Resilience

The Importance of Building Resilience among Students:

Have you ever wondered why some students are particularly good at dealing with ups and downs and seem to go through life with a positive attitude? There are many reasons why individuals approach life the way they do, but those who are good at coping and bouncing back from life challenges have something in common: Resiliency.

Resiliency is not one specific thing, but a combination of skills and positive attributes that individuals gain from their life experiences and relationships. These qualities help them solve problems, cope with challenges and bounce back from disappointments. Being able to deal with those setbacks and transitions is a key factor in positive mental health, as well as school and relationship success.

Resilience cannot occur without the presence of two factors - adaptive functioning and exposure to risk or adversity. A well-functioning child who has not faced high levels of adversity would not be considered resilient. An understanding of the 3 main components of resilience - risk factors, protective factors and competent functioning - is important when working with resilience in practice.

Resilience is a heterogeneous, multilevel process that involves individual, family and community level risk and protective factors. Risk factors are those that increase the likelihood of a negative outcome. Research suggests that it may be the number of risks and chronicity of risk exposure as being more important than any one risk factor.

Protective factors are those that reduce or mitigate the negative impact of risk factors and operate at the individual, family/school and community levels. They vary depending on the child’s age or developmental stage, as well as the type of adversity being faced. Examples of some protective factors include:

Individual Factors:

- Emotional self-regulation

- A sense of mastery and achievement

- Self-efficacy & self-determination

- A sense of control over outcomes

Family and School Factors:

- A close relationship with at least one caregiver

- A close and trusting relationship with an adult at school (i.e., teacher, administrator)

- Positive school climate, sense of belonging and attachment towards school

Community Factors:

- Involvement in sports and organized activities

- Access to support services

- External mentoring support

- Family connected to and integrated in community

To build resilience in children it is imperative to focus on reducing risk factors and enhancing protective factors, with adaptive functioning, competence or positive outcomes being key indicators of resilience. For more information on resilience, risk and protective factors, click here.

Determining how and which protective and risk processes are involved is imperative for designing effective interventions. One recent area of focus that has emerged as effective interventions for schools is the Strengths-Based Approach, which focuses on the strengths (e.g., competencies, resources, personal characteristics, interests, motivations) of the student, family or community. Strength-based practice is built on the premise that the developmental process is naturally oriented towards healthy growth and fulfillment, and that everyone has strengths to aid them in this process. Strength-based practice involves moving from the traditional focus of deficits to interventions that incorporate student’s abilities and resources. This is in line with research showing that most people will do well despite exposure to great adversity.

Enhancing resiliency using strength-based interventions is about incorporating and increasing a student’s assets. These assets include the resources, attributes and skills that help students recover from negative events or feelings, cope with challenges and adversity, and recognize when things aren’t going well. Examples of developmental assets that can be integrated into intervention with students include:

- Enhancing Relationships and Reaching Out Foster a positive school climate that creates a sense of belonging among staff and students. Encourage students to reach out to adults for support and strategies on how best to cope with life challenges.

- Emotional Skills:: Teach students self-regulatory skills and how to best cope with daily stresses and adverse situations. Encourage students to practice these skills and make the connection of the importance of learning to manage emotions so they don't overwhelm us.

- Competence: Skills: Teach students positive thinking and how to approach situations having a more balanced view of the world. Negative thoughts and emotions often cloud our abilities to process a situation and find solutions. Stepping back from a problem, having clarity, and listing all of the possible alternative thoughts are more effective ways of solving problems and influencing what happens in our lives. Reinforcing this with students can be a very powerful tool towards change.

- Optimism: Encourage students to assess situations with a positive and hopeful attitude. How we think about a situation will often impact its outcome. Viewing the world through a positive lens and promoting that situations can improve will have a significant impact on the result.

Be You is an example of an Australian initiative that operates in secondary schools and aims to foster the social and emotional skills youth in order to meet life’s challenges. For more information on this initiative, click here.

Another program that can be run with all primary or secondary school children is the Resilience Doughnut, created by Lyn Worsley, aimed at providing a process through which teachers, students and parents can build a child’s sense of optimism and hope. For more information in this area, click here.

For more information on resilience, please click here for links.

Anxiety Disorders

What is Normal Anxiety?

Anxiety is a normal feeling that all children and adolescents will experience at sometime. It may be experienced in the form of worry, fear, apprehension, or distress. Anxiety is a natural response that helps us avoid dangerous situations and motivate us to take action in solving everyday problems. It is adaptive in helping us to survive! Occasional nervousness and fleeting anxieties occur when a child or youth is first faced with an unfamiliar or especially stressful situation. This can serve as an important protection or signal for caution in certain situations. Life's challenges may be met with a temporary retreat from a situation, a greater reliance on parents for reassurance, a reluctance to take chances, and a wavering confidence. Children/youth may also experience some physical symptoms, but their anxious feeling will be appropriate for the situation and be time limited. Typically these concerns will resolve when the child learns to master the situation or the situation changes. The fears will then dissipate and have no lasting ill effects. Anxiety will look different depending on the stages of development:

Early Childhood

Normal anxiety in this period of development may be exhibited as the following:

- Separation anxiety (crying, sadness, fear of desertion upon separation) emerges around one year and declines over the next 3 years, resolving in most children by the end of kindergarten

- Fear of new and unfamiliar situations, real and imagined dangers from big dogs, to spiders, to monsters

- Apprehension with costumed characters, ghosts, and supernatural beings

- May struggle with the dark, the basement, closets, and under the bed

School Age & Adolescence

- Begin to fear real world dangers-fire drills, burglars, storms, illness, or drugs. With experience, they learn that these risks can exist as remote, rather than imminent dangers.

- Social comparisons and worries about social acceptance

- Concerns about academic and athletic performance

- Teenagers continue to be focused on social acceptance, but with a greater concern for finding a group that reflects their chosen identity

- Concerns about the larger world, moral issues and their future successes are common in later adolescence

When should be we concerned?

An anxiety disorder differs from normal anxiety in the following ways:

- It is more severe, intense, longer-lasting in duration, with significant distress

- It negatively interferes with child or youth’s ability to function or participate in typical activities of daily life or from what they want to do (i.e., school, relationships, emotional state)

- Occurs in the absence of or out of proportion to a threat or danger

- Associated with worrying about past and future

- Avoidance and escape become a child’s/youth’s automatic coping response

- Often accompanied by physical complaints (i.e., stomach aches, headaches, nausea)

- Can be maladaptive or unnecessary

Anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness among children and adolescents. However, as a result of stigma the majority will not seek professional help. Young women aged 15 to 24 are twice as likely to have anxiety disorders as young men (8.9% to 4.3% respectively). This disorder affects how one feels, thinks, behaves, and if left untreated can lead to depression, substance abuse, suicide or other mental health problems.

Warning signs of Anxiety Disorders:

-

Excessive, inappropriate anticipatory worry

-

Physical complaints (i.e., headaches, stomach aches, nausea, vomiting, heart palpitations, shortness of breath)

-

Demonstrating excessive distress out of proportion or in absence of the situation

-

Attention to threat, hyper-vigilance

-

Fast and sustained physiological arousal

-

Decreased attention or concentration, difficulty relaxing and sleeping

-

Easily distracted, irritable, speeding or slowing thoughts

-

Reluctance to go to school or other places, clinginess

-

Catastrophic, pessimistic thinking, trouble making decisions

-

Perfectionism, self-critical, very high standards that make nothing good enough

-

Demonstrating excessive avoidance, refuses to participate in expected activities, refusal to attend school

-

Seeks excessive reassurance (e.g., many ‘what if’ questions)

What causes Anxiety Disorders:

There is no one cause for an anxiety disorder. Genetics does play a critical role, as does exposure to a stressful environment. It is best to understand the causes of anxiety as resulting from a combination of an increased vulnerability to anxiety-- because of genetic or physiological makeup and exposure to a specific trauma or acute or ongoing stressor. Additionally, modelling and inadvertent reinforcement from adults (i.e., parents, teachers) can also increase vulnerability to an anxiety disorder. Research has shown that some parents of anxious children, especially if they are anxious themselves, have an anxious interpretation of the world, or view it as frightening. When parents hold this view of the world as threatening, they likely will suggest that their children avoid situations rather than approach them. Many adults want to protect child/youth from anxiety, but then they don't have opportunities to learn new skills or practice them.

Types of Anxiety Disorders:

What fuels Anxiety:

Anxiety is fuelled and maintained by the interconnections of three areas and can be best understood as a triad:

-

Thoughts

-

Physical arousal

-

Behaviours

Understanding the anxiety triad is extremely important when providing treatment and classroom/school adaptations. It is important to remember that anxiety is treatable! The main type of psychological treatment used to treat Anxiety Disorders is children/youth is called Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT). This evidenced-based treatment has been validated by research to provide successful results among children/youth. This form of treatment should always be delivered by trained mental health professionals.

For more information on the specifics of what fuels anxiety, click here.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT):

CBT teaches children/youth that rather than accepting anxious thoughts as truth, to generate more realistic versions of situations and their ability to cope with them. Children/youth then gradually face their fearful situations breaking the challenges down into small, manageable steps. They are then able to more quickly make into non-anxious interpretations of situations, and understand that avoidance of feared situations only makes matters worse. They learn instead that the only way to get past anxiety is to face it head on and approach situations until they become used to them.

CBT for most anxiety disorders addresses four main areas of interventions:

1. Psychoeducation:

-

Focuses on an explanation for how anxiety is triggered and maintained

-

Anxiety results from the brain misperceiving and exaggerating the risk in a situation and making them feel they need to avoid in order to survive

2. Cognitive Restructuring:

-

Guided to generate and evaluate the accuracy of self-talk; their internal dialogue or appraisal of a situation and identify thinking errors

-

Taught to "think twice" and identify the most likely thing that would happen in the situation, or the "what else's"; alternative thoughts

3. Breathing and relaxation techniques:

4. Exposure:

-

Challenging children/youth to face the situations and sensations and thoughts, which they may have come to avoid out of fear of feeling anxious

-

Done in small, manageable steps

-

Through exposing them in small steps they learn that they can feel anxious in a particular situation and still be okay

In the Classroom

Although most children/youth with anxiety disorders often benefit from specialized treatment, there are a variety of classroom and school-based adaptations that are useful:

- Help students identify worrisome thoughts:

When anxious, our thoughts tend to focus on all the bad things that might happen. Then we imagine the worst and worry! Often these anxious thoughts just paralyze and make us want to run away or hide. To help students identify their worrisome thoughts, suggest that they ask themselves:

- What am I thinking right now?

- What am I worried will happen?

- What bad things do I expect to happen?

- Encourage students to pay attention to their Automatic Thoughts:

Automatic thoughts are very short, quick thoughts or images that enter our mind almost automatically. They are part of our self-talk and we are often not aware of them. They set off our anxiety alarm. Worry Diary/box exercise: For two weeks, ask the student to write down their worries as they pop up. By writing them down, they don’t have to “keep track” of their worries in their head anymore. The student might find that a lot of worries don’t seem so powerful a few hours later, and especially after a good night’s sleep.

- Alternatives to Negative Self-Talk or Coping Statements:

Encourage students to replace their negative thoughts with some of these possible alternatives or coping statements:

- I am in charge, not my negative thoughts

- The world is a pretty safe place

- I can cope with most things

- I can feel anxious and still do it

- It’s just anxiety, it’s not dangerous, and it’s just temporarily uncomfortable

- These are just my anxious thoughts. I don’t have to believe them, I can just let them go

- Breaking down situations into small manageable steps:

For Example: A student is anxious about doing a presentation in front of the class. This can be broken up into a number of steps:

- Doing a short presentation in front of a friend

- Doing a short presentation in front of the teacher

- Doing a short presentation in front of the teacher and a few friends

- Being uncomfortable with uncertainty:

Help students become comfortable with uncertainty. This builds tolerance of it and helps to face the fear of not knowing. Examples of this strategy might be:

- Ordering something completely new at a restaurant

- Delegating an important part of a group school project to someone else

- Not asking a friend if he or she likes something new that you bought

- Telling yourself you’ll just have to see what happens at the party, rather than mentally rehearsing all your actions and conversations beforehand

- Helping students bring down the temperature:

- Relaxing activities

- Calm breathing exercises

- Muscle relaxation: tense and release

- Mindfulness breathing: 4-7-8; an example can be found here

- Visualizations and imagery

- Develop Healthy Habits:

- Increase sleep

- Increase exercise

- Healthy eating

- Decrease drug/alcohol use

For more information on anxiety, please click here for links.

Mood Disorders

What is Depression?

Depression is a serious mental health problem that can affect people of all ages, including children and adolescents. It is generally defined as a persistent experience of a sad or irritable mood as well as anhedonia; a loss of the ability to experience pleasure in nearly all activities that at one time were pleasurable. It includes a range of other symptoms such as changes in appetite, disrupted sleep patterns, increased or diminished activity level, impaired attention and concentration, and markedly decreased feelings of self-worth. Research has shown that children and youth who have depression may show signs that are different from adults.

Major depressive disorder, often called clinical depression, is more than just feeling down or having a bad day. It is different from the normal feelings of grief that usually follow an important loss, such as a death in the family. It is a form of mental illness that affects the entire person. It changes the way the person feels, thinks, and acts and is not a personal weakness or a character flaw.

Children and youth with depression cannot just snap out of it on their own. If left untreated, depression can lead to school failure, conduct disorder and delinquency, anorexia and bulimia, school phobia, panic attacks, substance abuse, or suicide. Depression often initially manifests itself in school, and as such educators play a critical role in its early detection. Once identified, educators are instrumental in referring the student to appropriate resources (e.g., psychologist, social worker, guidance counselor, local CLSC), as well as providing support and classroom adaptations.

Types of Depression

There are different types of depressive disorders, including:

Major Depressive Disorder also called major depression. The symptoms of major depression are disabling and interfere with everyday activities such as studying, eating, and sleeping. Children and youth may have only one episode of major depression in their lifetimes, but more often, depression comes back repeatedly.

Dysthymic disorder or Dysthymia is mild, chronic depression. Dysthymia is less severe than major depression, but it can still interfere with everyday activities. The symptoms of dysthymia last for a long time, 2 years or more. Children and youth with dysthymia may also experience one or more episodes of major depression during their lifetimes.

Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is another type of depression that usually begins during the winter months, when there is less sunlight and lessens during the spring and summer.

Prevalence and Risk Factors

Depression does not have a single cause. Several factors can lead to depression. Some people carry genes that increase their risk of depression, they may have a predisposition towards depression as it tends to run in families. But not all people with depression have these genes, and not all people with these genes have depression. Environment—one’s surroundings and life experiences—also affects the risk for depression. Any stressful situation may trigger depression in children and youth. Additionally, some children and youth have certain personality characteristics that make them more prone to depression.

Depression in Canadian Children and Youth

Mental health has been identified as a major health issue for students. It is estimated that, at any given time, approximately 15% of children and youth in Canada may experience a mental illness that inhibits healthy development. Fewer than 20% of those children and youth receive treatment.

Research has shown that the majority of mental health disorders affecting adults originate in childhood and adolescence. Each year, over one million people in Canada experience a bout of major depression, putting it on par in prevalence with other chronic, widespread health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. Estimates of depression in children aged 6 to 14 range from 2.7% to 7.8%, while rates for youth aged 15–18 is 7.6%.

How to Recognize Depression among Children and Youth

The way symptoms are expressed varies with a child’s developmental level. It is important to note that symptoms are usually a change in behavior from previous functioning. Characteristics of depression that usually occur in children and adolescents may include:

- Persistent sad and irritable mood

- Loss of interest or pleasure in activities once enjoyed

- Significant change in appetite and body weight

- Difficulty sleeping or oversleeping 4

- Physical signs of agitation or excessive lethargy and loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt

- Difficulty concentrating, unexplained irritability, or excessive crying

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide

- Frequent vague, nonspecific physical complaints (headaches, stomachaches)

- Frequent absences from school or unusually poor school performance

- School refusal or excessive separation anxiety

- Chronic boredom or apathy

- Excessive alcohol or drug abuse, increased risk-taking behaviors

- Withdrawal, social isolation, and poor communication

- Extreme sensitivity to rejection or failure and/or difficulty maintaining relationships

- Unusual temper tantrums, defiance, or oppositional behavior

The presence of one or even all of these signs and symptoms does not necessarily mean that a child or youth is suffering from depression. If several of the above characteristics are present, however, it could be a cause for concern and may suggest the need for a professional evaluation. Should educators be concerned about one of their students, it is suggested that they speak with a resource person at their school (i.e., guidance counselor, psychologist, social worker) or seek referral sources through their local CLSC.

School Adaptations for Students who are Depressed

As depression can have broad negative effects on students' academic work and socialization in school, there are a variety of accommodations and instructional strategies to increase students' engagement and success. The following school strategies can benefit children and adolescents battling depression:

- Teach problem-solving skills.

- Coach the student in ways to organize, plan, and execute tasks demanded daily or weekly.

- Develop modifications and accommodations to respond to the student's fluctuations in mood, ability to concentrate, or side effects of medication.

- Assign one individual to serve as a primary contact and coordinate interventions.

- Give the student opportunities to engage in social interactions and physical activity.

- Develop a home–school communication system to share information on the student's academic, social, and emotional behavior and any developments concerning medication or side effects.

- Give frequent feedback on academic, social, and behavioral performance.

- Teach the student how to set goals and self-monitor.

For more information on depression and other mood disorder, please click here for links.

High Risk Behaviours

Gambling

Gambling among Teens

According to Lynette Gilbeau, Research Coordinator at the International Centre for Youth Gambling Problems and High-Risk Behaviours at McGill University, for most individuals, gambling (for money) is an enjoyable form of entertainment and a socially acceptable recreational pastime. However, for some people, what begins as an enjoyable, relatively benign activity can escalate into a problem with serious social, emotional, interpersonal, physical, financial and legal ramifications.

Gambling, once thought to only be an adult activity, has clearly been shown to be popular among children and adolescents. Recent data suggest that upwards of 80% of youth report having gambled for money during their lifetime, with about 63% of Canadian youth reporting having gambled in the last year. At present, 4-6% of youth are experiencing a pathological gambling problem with another 10-15% being at risk for developing such a problem.

(Reference: Derevensky, J. (2011). Teen gambling: Understanding a growing epidemic. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.) Card games including poker, scratch tickets, betting on games of skill or sport are among the most popular forms of gambling among High School students. (Reference: Institut de la statistique du Québec, Enquête Québécoise sur le tabac, l’alcool et les drogues chez les élèves du secondaire, 2006)

The importance of prevention

Research suggests that age of onset is correlated with a gambling addiction. Many problem gamblers report having been introduced to gambling as early as 10 years of age. Early awareness and prevention programs are crucial.

McGill University’s International Centre for Youth Gambling Problems and High-Risk Behaviours has developed multiple award-winning gambling prevention and awareness materials for use with children as young as 8-9 years of age through adolescence. For more information, see: www.youthgambling.com.

La Maison Jean Lapointe provides free gambling awareness workshops in French and in English Quebec secondary schools. For more information, please click here.

When gambling becomes a problem

Gambling among students during school hours can be more difficult to detect and respond to than other risk behaviours such as alcohol and drug use. A group of young people gathered together at lunch time around a pair of dice or a deck of cards would not typically raise concerns among educators and the consequences of problem gambling may not be felt as immediately as drug or alcohol use. Some signs of problem gambling may include:

-

Spending more money than you intended;

-

Playing for longer periods than planned;

-

Gambling instead of taking care of your responsibilities;

-

Thinking about gambling a lot of the time;

-

Having difficulty reducing gambling;

-

Chasing one’s losses (gambling to recover prior losses)

It is interesting to note that according to a Quebec study, over 20% of High School students have received lottery tickets as gifts (as parents and educators, we need to be aware of our own gambling behaviours and beliefs.) (Reference: Institut de la statistiques du Québec, Enquête Québécoise sur le tabac, l’alcool et les drogues chez les élèves du secondaire, 2006)

A gambling problem can have significant impact one’s individual functioning (affective, cognitive, social and academic) as well as on mental and physical health.

For more information on gambling, please click here for links.

Non-Sucidal Self-Injury (NSSI)

What is Non-Suicidal Self-Injury?

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the deliberate and direct destruction of one’s body tissue, without suicidal intent and for reasons not socially or culturally sanctioned. The definition does not include tattooing and piercing (which are socially sanctioned), or substance abuse and eating disorders (which result in indirect harm). The most common age of onset for NSSI is early adolescence, and 14 to 20% of adolescents in school report engaging in NSSI at least once in their lifetime.

Why do students self-injure?

There are many reasons why students self-injure, but the most commonly reported function is as a means of coping with difficult, often overwhelming negative feelings (e.g., anxiety, stress, sadness, numbness). Other, less common functions include communicating feelings, self-punishment, and avoiding suicidal thoughts and urges.

How do I know if a student is self-injuring?

NSSI is typically a very secretive behaviour, and it is not unusual for adolescents to have difficulty talking about their injuries with others. It is not uncommon for no one to know about their NSSI. However, signs that a student is engaging in NSSI may include:

-

Unexplained cuts, burns, or bruises on the arms, legs, or stomach

-

The possession of razors, or other sharp objects

-

Continually wearing bulky, long-sleeved clothing regardless of the weather.

What should I do if I know a student is injuring themselves?

When first learning about a student’s self-injury, you may feel frightened, uncomfortable, shocked, or horrified by NSSI; these are normal reactions. However, it is important to monitor your reactions, as you may be the first person the student has spoken to about their injury. They are likely scared and nervous. Communicate calmly and respectfully, and let the student know that there are people who care for them and that they are not alone. Listen to the student, and try to understand what they are experiencing. Use non-judgmental language, and do not over react. Do not panic, and do not respond with shock or revulsion. Trying to threaten or coerce the student likely will not be effective, and may harm their trust in you. Do not ask about the details of the injuries, and do not allow the student to describe the behaviour, as this may trigger the desire to engage in the behaviour again. Do not talk about the student’s NSSI in front of other students, but do not promise the student that you will not tell anyone else, as you may be required to break confidentiality based on school protocol.

How is NSSI related to suicide?

NSSI and suicide are separate behaviours, and students that engage in NSSI may not have any suicidal thoughts. However, students who injure themselves may be at greater risk of suicide, and the school’s mental health professional should perform a suicide risk assessment in order to determine whether it is necessary to refer to emergency mental health services.

How do I help my student stop self-injuring?

We must always remember that students can stop injuring themselves. However, students who have used these methods for coping with their difficulties for a long time may find it very difficult to change their behaviour, and may be ambivalent about modifying their coping mechanisms. It is important for us to provide useful resources, and encourage students to find appropriate support from professionals who have experience helping adolescents who self-injure.

For more information on non-suicidal self-injury, please click here for links.

Substance Abuse

Adolescent brain development and substance use

Adolescence is characterized by significant growth and development and this, across a number of areas. Some behaviours such as those connected with increased independence and autonomy are characteristic of this period. Indeed, many of the behaviours associated with adolescence are related to cognitive maturation and can be explained by the fact that the adolescent brain is not yet fully developed. Research using brain imaging has helped us understand that the areas of the brain responsible for motivation and emotion develop earlier and consequently are more active during this period than those responsible for complex thought (e.g. judgment, planning and foresight) (Society for Neuroscience, 2007). Behavioural manifestations of this include difficulty with delayed gratification and impulse control, and risk-taking behaviours for which adolescents are notorious (Steinberg, 2007). The adolescent brain is also vulnerable because of the way it responds to various substances. Specifically, adolescents are less susceptible to the effects of alcohol, have shorter recovery times (less hangover) and are more sensitive to the effects of social disinhibition than adults, which reinforces substance use in social situations (Spear, 2002). What is more, the adolescent brain is more sensitive to potential damage brought about by the use of substances (Brown et al., 2000). For these reasons as well as those detailed above, experimentation with substances often occurs during this period. Adolescents are therefore more at risk to develop an addiction simply as result of the period at which they began.

Characteristics of adolescent substance abuse

Adolescent substance abuse is unique in terms of its risks which include rapid progression from first use to abuse and dependence (Winters, 1999), the short period between the first and second diagnosis of substance dependence (Spear, 2002), and the frequency of co-occurring disorders (Kandel et al., 1997, in Muck et al., 2001). Fundamentally different from adults, adolescents also have higher rates of binge drinking, less awareness regarding the problems associated to their use (Battjes et al., 2003) and an increased susceptibility to peer influence (Steinberg, 2004). Also relevant is the correlation between age of first use and rates of dependence: teenagers who start at an earlier age are more at risk of escalating to more serious and problematic use (Grant & Dawson, 1997). In view of the fact that adolescent problems related to substance abuse are more easily identified (e.g. attendance or behaviour at school, relationship with parents), and because most adolescents have not used as long as adults and have not yet experienced the physiological symptoms caused by their use, adolescents are more frequently diagnosed with substance abuse than dependence (Winters et al., 2001). Despite the numerous risks related to the use of substances by this age group, most adolescents who experiment can do so without it ever progressing to substance abuse and/or negatively impacting their lives. Moreover, many adolescents who are at risk will never use substances at all or develop problematic use (Winters et al., 2001; NIDA, 2003). These young people have developed healthy ways of coping that allow them to manage the powerful emotions they face.

Risk and protective factors

For others, it can be difficult to reduce or stop using drugs and alcohol, regardless of the severity of their problems. It can be incredibly challenging for adolescents to change their behaviour when they have been using to self-regulate and do not yet have the capacity to cope with the intense emotions they experience. For this reason, it is especially important to examine the reinforcing qualities of substance use and influences (family, peers) in relation to risk and protective factors which can act alone and/or in combination to shape behaviour. Risk factors are elements that increase the risk of developing an addiction (e.g. parental substance use, high stress, aggressive behaviour, poor impulse control), while protective factors reduce the likelihood that the an addiction will occur (e.g. stable living environment, parental support and involvement, academic achievement, community influence). Risk and protective factors can vary and are not the same from one person to the next; more than simply a physiological reaction to an addictive substance, drug use is often the result of multiple determinants in the teenager’s life (Swadi, 1999). One way to prevent substance use is to increase adolescents` resilience by enhancing protective factors and by reducing risk factors. Intervening early to address risk factors is especially important given the potential long-term impact on the adolescent not only in reducing risk, but also by helping foster positive behaviours (Ialongo et al., 2001).

Some family-related protective factors include:

-

a strong bond between children and their families;

-

parental involvement in a child’s life; and weight, tends to restrict food intake which leads to binge eating, evoking feeling of guilt which leads to purging behaviour (such as self induced vomiting, use of laxatives or diuretics) or compulsive exercise.

-

supportive parenting that meets financial, emotional, cognitive, and social needs; and

-

clear limits and consistent enforcement of discipline.

Other school-related factors include:

-

success in academics and involvement in extracurricular activities;

-

strong bonds with pro-social institutions, such as school and religious institutions

(National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (2003). Preventing Drug Abuse Among Children and Adolescents: A Research-Based Guide for Parents, educators, and Community Leaders, Second Edition.)

For practical tips and information on prevention and early intervention, click see our CEMH postcards dedicated to this topic.

For more information on substance abuse, please click here for links.

Suicide

Preventing Youth Suicide

Suicide is the second leading cause of death in youth aged 10-24. (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2012). A common reaction to learning about a student’s suicide or attempted suicide is to try to find a simple explanation, “his girlfriend dumped him” or “her parents were getting divorced”. While these may be contributing factors, suicide is actually a complex phenomenon involving the interaction of a variety vulnerabilities including personal, familial and psycho-social. Suicidal thoughts and behaviour represent the culmination of series of emotional stresses and losses resulting in being more fragile, vulnerable and overwhelmed with life challenges. These vulnerabilities and emotional stresses produce intense pain and suffering for the student which leads to increased irrational thinking and behaving. This irrational thinking results in the distorted conclusion that the only way to end the pain and suffering is suicide. The student is unable find reasonable solutions to their problems or recognize that suicide is not a reasonable choice. What further complicates the situation for youth is that unlike adults, they do not have a history of life experiences where they have been successful in overcoming difficult and challenging events. As well, a common perspective and fear is that the problem will go on forever, that the pain and unhappiness will last forever and that nobody can help them. Tragically, they may opt for a permanent solution to what may be a temporary problem.

Schools are called upon on a daily basis to deal with a variety of challenges and crises experienced by the members of their school communities. The probability that a school community, teachers, students, parents and administrators will have to deal with students’ suicidal crises is very real. Suicide is preventable as youth who are thinking of suicide frequently (over 80%) give warning signs of their distress. Teachers, parents and friends are in key positions to pick up these signs and get help. It is crucial for all school staff to be familiar with and watchful for these signs and to create an environment where youth in distress feel safe sharing this information as well as where peers are encouraged to share their concerns for a friend in difficulty. Effective suicide prevention engages the whole school community and is embedded in a positive school climate that promotes trustful student-adult relationships.

Warning Signs of Suicide

-

Threatening to hurt or kill themselves. Threats may be direct statements (“I want to die.” “I'm going to end it all.”) or indirect comments (“Nobody would miss me.” “Everyone will be better off without me.”)

-

Death and suicidal themes. These might be present in drawings, work samples, journals or homework.

-

Preoccupation with means. Increased interest in guns, knives, pills or other means of killing themselves.

-

Depression (helplessness/hopelessness). Comments or behaviours that indicate that the student is feeling overwhelmed by sadness and expresses a pessimistic view of their future. They see no reason to live or have no sense of purpose in life. They feel trapped and that there is no way out.

-

Reckless behaviour. Engaging in risky activities in an impulsive and non-reflective manner indicating little concern for their own safety. Increased alcohol or substance abuse.

-

Making final arrangements. Putting things in order or giving away prized possessions like clothing, skateboard, I-Pods, jewellery, etc.6

-

Sudden and dramatic changes in mood or personality. Changes can include withdrawal from friends and family, skipping class and loss of involvement in activities once important or enjoyed. Changes may also be seen in terms of more anger, rage, or seeking revenge.

-

Changes in physical habits and appearance. Changes include inability to sleep or sleeping all the time, sudden weight loss or gain, disinterest in appearance and hygiene, anxiety and agitation.

-

Inability to concentrate or think clearly. Such problems may be reflected in schoolwork, household chores or even in conversations.

Risk Factors

-

Mental health difficulties including depression, anxiety and trauma

-

Family stress and dysfunction

-

Experience of a major loss, such as death of a loved one, divorce and unemployment

-

Situational crises or experience of major changes in their life

-

Substance abuse

-

Exposure to suicide or previous attempts

Protective Factors

-

Family support and cohesion, including good communication

-

Peer support and close social networks

-

Cultural or religious beliefs that discourage suicide and promote healthy living

-

Adaptive coping and problem-solving skills

-

General life satisfaction, good self-esteem and sense of purpose

-

Access to effective health and mental health service

School-Based Protocols

In order to respond effectively to troubled students who threaten or attempt suicide, development of detailed school based protocols are required. Protocols should clearly specify who is to be contacted if a student demonstrates suicidal behaviour and what specific steps need to be taken. Protocols clearly delineate specific roles for crisis intervention for educators and mental health professionals within schools.

A suicide is one of the most painful and disturbing events for a school community. Development of protocols to guide interventions (postvention) in schools in the aftermath of a death by suicide outlines how to effectively provide stability and emotional support to those affected by the tragic event. Protocols detail how to deal with misinformation and rumours that can increase distress putting other students at risk and increasing the risk of suicide contagion. Each school can develop crisis intervention and postvention procedures and protocols consistent with their school culture and climate with the support of resources available in their school board and community.

Guideline for Educators

When a youth who is thinking of suicide comes to you or comes to your attention from peers or other school personnel take immediate action to keep the student safe. Under no circumstances should the student be left alone (even in the washroom).

Be aware of who can help. Schools should identify the individuals who are trained to act on all reports from teachers, other staff and students about a student who may be suicidal. These individuals are usually the school psychologist, guidance counsellor, nurse or social worker.

Collaborate with colleagues. Having support and consultation from another professional or administrator is both reassuring and prudent. The steps to getting the most effective help for the student can at times be involved (who needs to be informed? what are the most effective services available? how to keep the student safe?) and extend beyond the school to home and the community.

Mobilize a support system. It is important for the student to feel some control over their fate. To assess the student’s support system it is sensible to ask “who do you want or who do you think can be there for you?” Solicit the student’s assistance where appropriate and inform them of what you are going to do to get them help at every step of the way.

POSTVENTION

For more information on suicide prevention, please click here for links.

Trauma

What is a traumatic event?

A traumatic event can be any stressful incident or series of incidents that precipitate significant anxiety/arousal reactions within the school community. It is recognized that in a school’s daily life there are a multitude of events that are anxiety producing and stressful and that require a managed, effective response. However, there exist a range of events that require a more directed approach in order to ensure the safety of the school community and to reduce the intensity of emotional reactions to these events. Some of these traumatic events include:

- violence and threats of violence

- tragic accidents resulting in severe injury or death

- suicide

In these circumstances, an effective response from the school is required to diffuse potentially volatile situations, to give direction to staff and to limit further negative consequences. Evidence-based practices indicate that specific interventions are needed within the school community to avoid panic, to attenuate negative reactions and to return the school to normal operation as smoothly as possible. Postvention following a traumatic event involves two important and closely intertwined activities undertaken to maintain or restore order and to provide emotional and psychological support. Administrative measures such as informing staff members of the tragic event and developing with them a plan of action clearly demonstrates that the situation is under control and that the school community is safe and secure. Emotional and psychological support is provided to help members of the school community cope the troubling thoughts and feeling that result from exposure to a tragic situation.

What schools can do

Traditionally, during a crisis or following a traumatic event, schools have called upon the services of outside trained mental health professionals to provide psychological support. Recent research in this area suggests that professionals (psychologist, guidance counselor, special needs consultant, spiritual animator, school social worker, etc.) who are familiar with the school environment and are known to the school community would be best suited to provide support most consistent with a school’s climate and culture.

First Response

Following a traumatic event, it is important that both administrative and psychological interventions are based on an analysis of the situation, evaluation of the various needs with a particular focus on individuals who are most vulnerable and the implementation of a variety of interventions that correspond appropriately to the identified needs. An evidence-based framework for providing appropriate support following traumatic events is Psychological First Aid. This model is centered on providing comfort, care and aiding natural recovery. The 8 components of Psychological First Aid are:

- contact and engagement

- safety and comfort

- stabilization

- information gathering: current needs and concerns

- practical assistance

- connection with social supports

- information on coping support

- linkage with collaborative services.

The care and concern expressed to the students by teachers and a principal who know them best and are close to them on a daily basis provides this type of emotional and psychological support. Sharing a few moments to cry together and to be held and hugged by your teacher an extremely powerful intervention.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network and the National Center for PTSD has made available the Second Edition of Psychological First Aid Field Operations Guide. Refer to this site.

In providing support to schools following a traumatic event, it is important to recognize that not everyone in a school community experiences a tragic event in the same manner. When a school community is exposed to a traumatic event it is completely normal for individuals to experience a wide range of reactions, including physiological, behavioural, cognitive and emotional. Generally, three types of responses are most likely to occur. Individuals who are closely involved in a tragic event may commonly react with shock, disbelief and fear, which give way to feelings of anxiety, anger and sadness. These responses are normal and temporary stress reactions. While temporary stress reactions can be expected, some individuals may develop more acute stress reactions or subsequently Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. When the traumatic event involves a death, it is expected that some individuals in the school community will experience feelings of intense sadness, loss and emptiness or grief reactions. Grief reactions may be experienced by those individuals who have a very close and special attachment to the deceased person. Initial grief reactions may be replaced by more complicated and long term grieving. When a death occurs by suicide, vulnerable individuals within the school community may develop a heightened sense of helplessness and despair and may experience suicidal reactions.

Many factors influence the nature and severity of these reactions in individuals including proximity to the event or the victims, pre-existing vulnerabilities (psycho-social or mental health problems), personal experiences (a recent illness or death of a loved one) and for students, their cognitive and emotional development. Recognition of the various types and intensities of reactions holds important implications for planning realistic and effective interventions following a traumatic event. Clearly, any interventions that are put into place should be based on an analysis of the differing individual needs. Massive school wide interventions that do not take into consideration varying individual needs can result in increased levels of discomfort and distress in a school. Particular attention needs to be paid to suicide postvention as research studies have suggested that interventions that inadvertently glorify, dramatize or validate suicide as a credible solution to one’s problems increase the probability of contagion and increase the risk of suicidal crises.

Most students and staff recover from traumatic events with little formal intervention by using their traditional support system such as parents, family, friends, religious affiliations, etc. One of the prime objectives of school based interventions is to facilitate and encourage these naturally occurring support systems. The reality of today’s society is that a child’s teacher plays a significant role in providing emotional and social guidance and support to the students when they are faced with challenging situations. Feedback from teachers has indicated that they believe they are in the best position to offer students the support they need following a crisis, but they sometimes feel unsure about what to say or how to intervene. As well, while schools are encouraging students to speak to their parents about their feelings and reactions, some parents may feel poorly equipped to respond appropriately. In order to help support teachers and parents, fact sheets can be prepared by professionals on topics that include the warning signs of distress, what to look for in children’s reactions or how to respond to their questions and how to provide reassurance.

|

We tend not to talk about illness, accidents or death. Understandably, these are not pleasant topics. However, when tragedy strikes we are shocked and may feel unprepared to deal with the situation. Almost everyone affected, whether administrator, teacher, psychologist, parent or student, has a similar initial reaction and questions how they are going to be able to manage the situation. The truth is, everyone does manage and does cope. Some handle it a little bit better, some not quite as well, but everyone does manage. We may feel that the next time we are confronted by a similar situation we will be better prepared. However, we always hope that there is no next time.

|

|

For more information on trauma, please click here for links.

Eating Disorders

Eating Disorders: A primer for School Professionals

The incidence of Eating Disorders, especially Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia, is believed to be on the increase: a growing number of people, mostly adolescent girls and young women suffer from these illnesses.

School Professionals play a key role in identifying those who are struggling with these problems, given that early detection often is associated with better outcomes.

The starvation, chaotic eating and purging strategies associated with eating disorders affect all aspects of an individual’s life including their physical health, their academic experience and their relationships with family and friends.

As Eating Disorders often develop during adolescence and early adulthood, the illness disrupts many developmental tasks associated with identity formation and autonomy which in turn has a significant influence on future development. Those individuals whose illness takes a more chronic course become increasingly frail and isolated.

Families are also negatively affected by these illnesses; family relationships become more strained, family tensions often increase, and feelings of helplessness and powerlessness become more common.

Our society values performance, competition, body shape, and youthfulness. Eating Disorders tend to reflect the pursuit of these ideals at the expense of an individual‘s health, personal fulfillment and satisfaction.

Types of Eating Disorders

-

Anorexia Nervosa is characterized by a highly restrictive eating pattern, compulsive exercising, an intense fear of becoming fat, disturbed body image and an inability to maintain normal body weight.

-

Bulimia Nervosa is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by purging. A person with bulimia tends to be preoccupied with body shape and weight, tends to restrict food intake which leads to binge eating, evoking feeling of guilt which leads to purging behaviour (such as self induced vomiting, use of laxatives or diuretics) or compulsive exercise.

-

Compulsive overeating or Binge eating is characterized by overeating and using food to avoid feeling states, often leading to obesity.

Who is at risk for developing an Eating Disorder?

The cause of eating disorders is believed to be multidimensional; a variety of biological, psychological, and social factors contribute to its development. Some of the major risk factors that predispose an individual to developing an eating disorder include:

-

Being female

-

Having a perfectionist, rigid and risk-avoiding personality

-

Excessive dieting

-

Family history of obesity, eating disorders, substance abuse, or depression

-

Sexual or physical abuse experiences

-

Bullying and harassment experiences

-

Competitive sports where body shape and size are a factor

Guidelines for School Professionals

-

Be aware of the warning signs of an eating disorder (E.D.)

-

Be compassionate yet straightforward: Tell the student directly that you are concerned about him or her. Present the specific reasons for your concern emphasizing health, apparent unhappiness, conflicts at school, low academic performance and obvious evidence of eating disorders, i.e., loss of weight, binging, purging, and compulsive exercising.

-

Be patient: It is important to understand that when you approach someone with an E.D., the person may not welcome your expression of concern and may even react with anger, hostility or denial. Be prepared that the student may need some time before accepting your concerns and taking your advice.

-

Let the student know that you care and are willing to talk about eating behaviours when she/he is ready.

-

Avoid commenting on his/her appearance and weight. Don’t dwell or engage in food related discussions.

-

Examine honestly your own attitudes about body image, weight issues and size, so as not to convey any fat prejudice, or exacerbate the student's desire to be thin.

-

Know your limits and avoid over-involvement in trying to help a student with an E.D.

-

Encourage the student to seek professional help.

Prepared by: Dorita Shemie, MSW, social worker, Eating Disorders Program, Douglas Mental Health Institute

For more information on eating disorders, please click here for links.

Personality Disorders

What is Personality?

Every person has an individual personality made up of traits that come from both one’s genetic make-up and life experiences. The word ‘personality’ usually refers to the pattern of thoughts, feelings and behaviour that makes each of us who we are. Most people do not always think, feel and behave in exactly the same way – it depends on the situation, one’s past experiences, the people one engages with, their mood and other similar circumstances. However despite this, an individual’s general pattern of behaviour is also somewhat predictable. By adolescence, people tend to behave in particular ways that are unique to them, thus reflecting their individual personality. For example, a person who is described as having an ‘outgoing’ personality tends to be talkative, social and engage easily with people around him/her.

While personality remains relatively stable after early adulthood, it is adaptable to one’s life experiences. Most people tend to be able to learn from past experiences, change their behaviour and cope with challenging circumstances regardless of their dispositional personality traits.

What is a personality disorder?

A personality disorder is a type of mental disorder that occurs when one’s pattern of thinking, feeling and behaviour is extreme, inflexible and maladaptive. It is also often associated with significant distress to the person and those around him/her. There are 10 different types of personality disorders that are categorized into 3 groups: Cluster A: odd and eccentric behaviours, Cluster B: dramatic and erratic behaviours, and Cluster C: anxious and fearful characteristics.

Categorization is based on the specificity and pervasiveness of the behaviour, as well as on the impact it has on daily functioning. Typically, diagnosis of a personality disorder requires a comprehensive evaluation by a psychiatric team, and is not diagnosed until adolescence or early adulthood.

Warning Signs For Educators

There are many warning signs that emerge in childhood that are known to be predictive of personality disorder development. Often, these warning signs can be identified through a child’s classroom behaviour. Although it is important to note that symptoms may vary widely and do not always result in the development of a personality disorder.

Listed below are common warning signs, organized within the 3 categories, which may be seen by a teacher in a classroom. It is important to note that while many behaviours are specific to the category they fall in, others may overlap between categories.

Cluster A:

Characterized by: odd and eccentric behaviours. Disorders: schizoid, schizotypal, and paranoid personality disorders. Common precursors: Lack of close friends, social anxiety, academic underachievement, peculiar thoughts, language and fantasies, interpersonal sensitivity.

Cluster B:

Characterized by: dramatic, emotional and erratic behaviours. Disorders: narcissistic personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder, borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. Common precursors (Narcissistic, histrionic and borderline): failure to emotionally respond to others, lack of dependency, tendency to think one deserves care and attention, failure to show gratitude, self-dramatization, attention seeking, emotion deregulation, anger episodes, vulnerability to separation, anxiety and mood problems, depression, self-harming behaviour and problems with eating and sleeping. Common precursors (Antisocial personality disorder): aggression towards people and animals, destruction of property, serious violation of rules, running away from home, deceitfulness or theft. Often manifested as conduct disorder in younger children.

Cluster C:

Characterized by: anxious and fearful characteristics. Disorders: obsessive compulsive, dependent and avoidant personality disorders. Common precursors: continuous writing and erasing, tearing up homework, desiring control, over-compliance to rules, over-conscientiousness, clingy behaviour, fear of separation, hypersensitivity to negative evaluations, social inhibition, feelings of inadequacy and fear of being shamed or ridiculed.

Risk Factors

It is not entirely clear how personality disorders develop. However, research on personality disorders has suggested a variety of risk factors that are both environmentally and genetically based. It is often a combination of these risk factors that contribute to the development of a personality disorder. Risk factors include, but are not limited to the following:

-

Difficult childhood circumstances such as poor parenting, lack of attachment, neglect or abuse

-

Early and severe trauma during childhood (e.g., parental death, social isolation)

-

Familial financial difficulties (e.g., low socioeconomic status, single-parent families, welfare support)

-

A family history of personality disorders or other significant mental health problems (e.g., psychopathology, substance abuse) can lead to a predisposition to develop a personality disorder.

How to support students showing signs of personality disorder development:

-

Collaborate with psychiatric treatment team, school mental health professionals and parents in developing strategies that can best support the needs of the student

-

Become attuned to the associated symptoms or warning signs that trigger symptoms (e.g., anger outbursts) to prevent them from occurring

-

Help identify coping strategies such as: talking to someone trustworthy, writing your feelings down, learning to walk away, positively reframe conflicts, consider the bigger picture, and setting smaller goals

-

Offer emotional support, understanding, patience, and encouragement

-

Implement support systems that are consistent with the ones the family may be using at home

-

Promote pro-social interactions with peers at school

-

Allow the student a “Cool-Down’ break

-

Listen actively and ask open-ended questions to the child when asking about a conflict (e.g., what do you think made you angry when interacting with Billy?)

-

Increase the ‘reinforcement quality’ of the classroom (e.g., increase motivation to engage in academic activities by structuring lessons or assignments around a topic of high interest)

-

Have a positive spin on teacher requests (e.g., “I will help you with your work once you take a seat” compared to “I will not help you until you take a seat”)

-

Enforce positive reinforcement strategies for constructive, cooperative and helpful behaviour

-

Problem solve with the student for solutions to problems the student may be experiencing

References used:

Bernstein, D. P., Cohen, P., Skodol, A., Bezirganian, S., & Brook, J. S. (1996). Childhood antecedents of adolescent personality disorders. The American journal of psychiatry, 153(7), 907.

De Clercq, B., & De Fruyt, F. (2007). Childhood antecedents of personality disorder. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(1), 57-61.

ve Ergenlerde, K. B. Ç., & Bulguları, Ö. (2015). Precursors of Personality Disorders in Children and Adolescents. )

For more information on personality disorders, please click here for links.

Psychotic Disorders

Psychotic disorders are medical conditions in which the individual experiences a psychosis. Psychosis or a psychotic episode is considered a serious mental health problem that is associated with symptoms that can cause a severe disruption to perception, thinking, emotion and behaviour. More specifically, symptoms of psychosis prevent the person from thinking clearly, being able to tell the difference between reality and their imagination, and acting in an appropriate, and often, odd manner. The person experiencing a psychosis often feels distressed and overwhelmed and had trouble functioning in everyday life. Recognizing and identifying the warning signs is very important because early intervention can reduce the severity of a psychotic episode, help slow the progress of the illness as well as reduce its impact on the family.

Symptoms associated with a psychotic disorder

-

The presence of a change in the person’s usual eating and sleeping habits, moodiness, lack of motivation or ability to concentrate and to maintain previous levels of functioning at work, school or everyday activities.

-

Presence of hallucinations: the person hears, sees, (or in some cases smells and feels) things that are not actually present in his/her environment. For example, a common hallucination is when one hears voices in their head.

-

Delusions may also be present: in which the person believes things that are objectively unfounded and are often strange and bizarre. For example, believing that your friends are secretly reading your mind and plotting against you; or believing that your food is being poisoned.

-

Thinking can often appear disorganized and the person may appear confused and act in a strange manner.

-

Symptoms of anxiety and depression are often present.

-

Symptoms may develop gradually (sometimes over months) or appear more suddenly.

Treatment

Treatment for psychosis usually involves using a combination of ongoing therapies:

-

Antipsychotic medicines which can help relieve symptoms of psychosis. Some people may only need to take antipsychotic medicines on a short-term basis. Other people may need them for months or, in some cases, years to prevent symptoms reoccurring.

-

Psychological therapies: A variety of therapies and approaches have been shown to be successful in helping both the person with the psychosis and the family. Psychotherapies (such as cognitive behaviour therapy) can help the individual deal with problem of thinking, reasoning, perception and problem-solving. Family therapy and psychoeducation help the individual and their family better understand the disorder, its implications and learn about strategies to manage the various challenges. Group therapy is helpful in providing peer support to learn about healthy social interaction and to develop strategies for coping with demands of daily life (work, school, social and community).

-

Social support: Helping the person connect socially is essential. In addition, providing support to address needs in terms of education, employment or accommodation is often required in order to help the individual regain appropriate functioning in the community.

Psychotic disorders in children and adolescents

Psychotic disorders are rarely diagnosed in childhood. However, later in adolescence these disorders can become more prevalent, although still rare (estimated 1% prevalence). Teenagers with a psychotic disorder or experiencing a psychotic episode often have other mental health problems such as depression, anxiety and even suicidal behaviour. In addition, an adolescent diagnosed with a psychotic disorder often experiences problems with cognitive functioning (difficulty processing information, poor attention and memory), and at times even difficulties with language and motor skills. These problems can interfere with the adolescent’s ability to function independently and can lead to problems with academic achievement and impaired social functioning.

What can parents and families do to help?

-

Recognize that your teenager needs support at many levels (family, school, social) and that support may need to be long-term.

-

Monitor medication as the teenagers may have difficulty (due to side effects, denial of the disorder, or not wanting to be different) and address any problems with the medical management team.

-

Parents need to encourage and help promote healthy living such as good nutrition, adequate amounts of sleep and physical activity.

-

Try to find ways to reduce stress in your child’s environment (such as reducing stimulation, ensuring demands are not overwhelming).

-

Help your child/teen recognize that you are there for them (for example, you may say: “how can I help you?”; “I am here for you, I care”, etc.).

-

If your child is experiencing odd symptoms (such as hallucination) stay calm and be understanding and non-judgmental.

What can schools do to help?

-

f the student has been absent from school for a lengthy period, it is important to help and support him/her during reintegration into the school. The student may require gradual reintegration.

-

In school, a connection should be made with a support staff member (psychologist, counsellor etc) both for personal support as well as to facilitate in- school remedial support when necessary.

-

Support in school would include:

-

addressing the anxiety and stress related to academic work (for example, providing down time and opportunities relax or regroup when necessary; allowing extra time to complete work and a reduced load).

-

providing academic or educational support for the student.

-

helping to facilitate positive interactions with peers and promote social interactions.

-

Help in providing access to community supports is also important.

For more information on psychotic disorders, please click here for links.